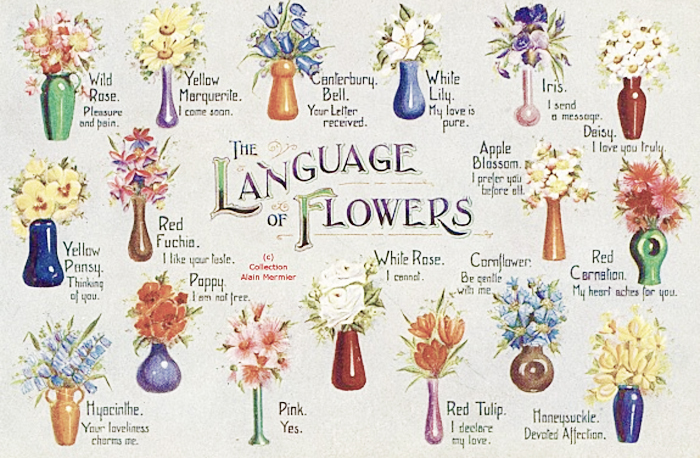

The Victorian Language of Flowers is founded on the notion that flowers serve as symbolic illustrations of abstract concepts. It is still acknowledged today by florists who pair sentiments to their proper flowers.

The term 'floriography' was coined during the Victorian era to define the symbolic meanings attributed to various flowers. Victorian culture was not the first to associate meaning with flowers. The Japanese have an older tradition named 'Hanakotoba' that informs what flowers are used in the art of 'Ikebana' - floral arrangements emphasizing sculptural effect in a style that Westerners might define as minimalistic.

In the early eighteenth century the language of flowers as it would come to be known was already well recognized throughout Europe. A fad for all things Oriental lead some authors to claim that floriography originated with selam, and method used to communicate meaning through flowers and other objects according what other words they rhymed with. The story went that harem ladies used this language to express otherwise secret desires to their lovers, however this appears to be a fanciful notion challenged by such writers of the time as Joseph Hammer-Purgstall, a German authority on the Orient.

Other historians attempted to trace the origin of floriography to Turkish tradition, emphasizing the letters of Lady Mary Wortley, wife of the British ambassador to Constantinople, who in 1718 wrote:

"There is no colour, no flower... that has not a verse belonging to it; and you may quarrel, reproach, or send Letters of passion, friendship, or Civility, or even of news, without ever inking your fingers."

While selam did exist, it seems to have been a playful pastime played among women within the harem, not a means of communicating forbidden emotions to men outside it.

Despite it's alleged connection to more exotic lands, the European tradition of associating flowers with higher concepts had already established itself in the Medieval and Renaissance gardens of the past. The term 'hortus conclusus' is Latin for an enclosed garden, and is an emblematic attribute of the Virgin Mary; the flowers grown there were intended to express her holy attributes. Various flowers had long been associated with the virtues certain saints, constituting the iconography through which they were portrayed and recognized by the faithful. The Victorian language of flowers grows from that tradition, expressing the attributes of flowers in a secular context.

Joseph Hammer-Pugstall's "Dictionnaire du language des fleurs" (1809), appears to be the first published list associating flowers with symbolic definitions. Yet the first dictionary of floriography appears in 1819 when Louise Cortambert, writing under the pen name 'Madame Charlotte de la Tour,' wrote Le Language des Fleurs, a small but well circulated book. Others followed, often with variant definitions. This inconsistency aided their popularity, since one had to fill his or her library shelf with as many books as there were meanings, lest miscommunication arise.

In its heyday, this language was easily express with nosegays (also called ‘tussie mussies’ and ‘posy’), bouquets commonly held by proper women to alleviate the effects of lowly odors. This custom evolved to include such flowers as expressed myriad concepts and desires. This floral language came to be expressed throughout Victorian life, as such flowers were depicted on fabric, china, stationary, jewelry, and even in the naming of daughters for whom certain expectations and

characteristics were sought.